Students at two-year colleges at risk of food insecurity during economic downturn

|

A version of this post was originally published on UrbanWire.

Students attending two-year colleges are more likely to be food insecure than other adults, particularly during economic recessions. Though we don’t identify the underlying causes of this trend, the high levels of food insecurity among two-year students should push policymakers to reexamine how the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) and other supportive services can best assist these students, who tend to operate at the margin between college and work.

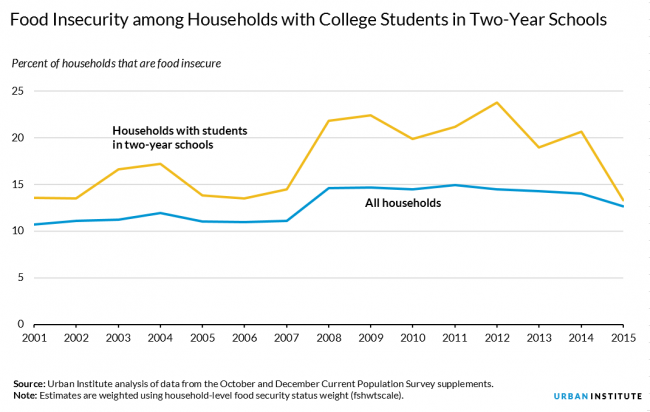

At the start of the Great Recession, the share of food insecure households rose substantially, from 11.1 percent in 2007 to 14.6 percent in 2008. Among households with two-year college students, however, we estimate that food insecurity rose even more dramatically, from 14.5 to 21.8 percent in just one year.

We can’t identify exactly why students at two-year colleges are more at risk of food insecurity during an economic downturn. One possibility is that those who were already attending two-year schools became more food insecure because of reduced family support or the loss of a part-time job. Another explanation is that economically vulnerable individuals (such as those who have lost jobs) may be more likely to enroll in two-year schools. A third possibility is that two-year schools may increase their charges (tuition and fees) or reduce the supports they offer students, such as child care or access to administrative assistance, during recessions.

Regardless, this trend calls for a closer look at how SNAP works for two-year college students. Participation in SNAP has been found to reduce the likelihood of being food insecure, at rates ranging from 12.8 to 30.0 percent. Total spending on SNAP more than doubled from 2007 to 2010, substantially reducing the number of households that would otherwise have been food insecure.

Most college students are not eligible for SNAP benefits. If an individual is enrolled in higher education at least part-time, they are only eligible if they work at least 20 hours a week (or participate in work-study), are caring for a dependent child younger than 12, are unable to work because of a disability, or meet other requirements.

The SNAP student exemption is, on its face, a reasonable policy—if a student has access to a campus-based food plan or assistance from family while enrolled in school, they should not be eligible for SNAP, even if their own earnings are low. However, the trends we identify in our research indicate that students in two-year schools may need the additional support from programs like SNAP, particularly during periods of economic downturn.

Demand for education is counter cyclical; demand goes up during recession periods when job opportunities are low. Policymakers should be prepared to support the expansion of higher education in periods of economic downturn, particularly for low-income individuals and those in two-year colleges. Attainment of a two-year degree is broadly associated with substantial earnings gains, but students won’t be able to persist through college if they cannot meet their basic needs.

State and federal policymakers have several options for supporting two-year students during the next economic downturn:

- Expand SNAP eligibility to more education programs: Though current federal eligibility guidelines disqualify many students, including many at two-year schools, states have some flexibility in how they administer SNAP. For example, in Massachusetts, administrators expanded eligibility to those enrolled at least half time in a career or technical education program at a community college. In 2010, advocates estimated that roughly a third of all students enrolled in Massachusetts community colleges were potentially eligible for SNAP based on their participation in these programs.

- Increase grants for higher education: Expenditures on federal Pell grants for low-income students generally rose from 2008 to 2010, as the number of Pell recipients increased during the recession. Policy changes, such as an increase in the maximum Pell grant and the availability of year-round Pell, also contributed to this increase, providing additional supports for students. But federal policymakers should be wary of how state legislatures may respond to financial aid expansions during a period when their own budgets are under pressure. If states choose to pull back their grant assistance as federal aid increases, it’s possible that low-income students could face overall declines in aid.

- Promote wraparound student supports, such as Single Stop: Wraparound student support programs, such as the nonprofit Single Stop U.S.A., connect students to programs and resources that address nonacademic barriers to college completion. The Single Stop program has demonstrated success in increasing college persistence rates for students who use their services. Programs like these, which help students navigate public and private social safety net resources, could be expanded through support from state or federal policymakers.

During the Great Recession, legislators expanded the social safety net to reduce the impact on US workers and their families. When the next recession occurs, policymakers should consider quick implementation of policy levers that support the basic needs of low-income students at two-year schools. Having a plan in place before the next downturn could help policymakers act more quickly to buffer the negative impacts on individuals working to improve their educational attainment.

Related Projects

-

September 15, 2016

|Has Evidence

| -

Mental and Behavioral HealthCalifornia Diversion: Mental Health, Racial Equity, and Criminal Court

September 1, 2021

|Has Evidence

| -

Community Justice and Public SafetyAre Cities and Counties Ready to Use Racial Equity Tools to Influence Policy?

December 15, 2018

|