What California’s 2015 Measles Outbreak Can Teach Us About Vaccine Policy

|

Last month, a familiar headline made its way across the country’s news outlets—measles is back.

The first case was confirmed in Clark County, Washington and quickly spread to nearby counties. As of February 27, 2019 there have been 70 documented cases in the Pacific Northwest. The majority of the cases are among unvaccinated children under the age of 10.

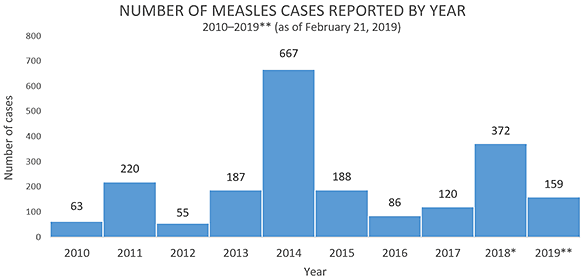

But this is no isolated incident. Measles has been cropping up with troubling frequency in the last several years (see Figure 1), and in 2015, California experienced its most severe measles outbreak in over a decade. With its epicenter at the Disneyland in Orange County, the outbreak ultimately infected 110 Californians and at least 15 others in neighboring states, many of whom were unvaccinated.

FIGURE 1

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html

*Cases as of December 29, 2018. Case count is preliminary and subject to change. **Cases as of February 7, 2019. Case count is preliminary and subject to change. Data are updated weekly.

Measles past and present

In the early 1900s, measles was extremely common. It infected nearly every child by the time he or she reached the age of 15, until a measles vaccine was developed in the 1960s. Widespread immunization coverage was achieved by the 1990s, and in 2000, measles was declared eliminated in the U.S.

In the years following, however, fewer and fewer Americans perceived the disease as an imminent threat. Adding in the availability of non-medical vaccine exemptions and misplaced fear over vaccine safety, progress towards increasing vaccine coverage grew stagnant, and even declined in areas across the country.

Outbreaks are more likely to occur when disease is introduced into a population in which exemption rates are high, and coverage levels lag below the level needed for herd immunity. The outbreak in California occurred in a county with historically high rates of non-medical exemptions for vaccination. Among those who were unvaccinated, yet vaccine eligible, roughly 67 percent had obtained a personal belief exemption from vaccination.

A similar story rings true for the recent outbreak in Washington State. According to Washington’s state health department data, Clark County had an overall measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination rate of just 83 percent in 2017. Over two-thirds of reporting schools (69%) had a coverage rate that fell below the level needed for herd immunity.

California repeals non-medical exemptions

The 2015 measles outbreak was eye-opening for California. The state responded by repealing all non-medical exemptions (both religious and philosophical) within the year.

To find out whether the repeal of non-medical exemptions was associated with an increase in uptake of vaccines required for school entry, our team at George Washington University evaluated California’s new policy and tracked vaccination rates from 2012 to 2017 in California and a group of control states that did not have any changes in their exemption provisions.

Our research reveals that MMR vaccination coverage rose almost 3 percentage points following the repeal. Other required vaccinations (DTP, Polio, and Hepatitis B) increased around 2 percentage points.

However, we also found that the policy came with unintended consequences. As rates of non-medical exemptions declined, medical exemptions rose a shocking 400 percent.

Medical waivers are permitted in every state, but they are reserved for individuals with genuine contraindications to vaccination and require written certification by a licensed physician. Prior to the repeal, the rate of medical exemption in California was merely 0.5 percent. After the repeal, rates increased to 2.5 percent. Even more startling, the largest increase in medical exemptions occurred in counties that previously had high rates of non-medical exemptions, suggesting that vaccine-hesitant parents started shopping for doctors who would sign off on a medical exemption waiver.

What can we learn from this?

The response to California’s new immunization policy has important public policy and public health implications—both for the state of California and for other states across the U.S. looking to enhance immunization coverage.

First, if parents can substitute between medical and non-medical exemptions, lawmakers need to think carefully about how the exemption process can be monitored to ensure that medical waivers are preserved for children who truly need them.

Second, unvaccinated children (along with anti-vaccination sentiment) tend to be clustered in counties and schools with high rates of exemption. Our research highlights that the concentration of exemptions increases the possibility of future outbreaks—even when non-medical exemptions are eliminated.

Washington State lawmakers are already drafting legislation to remove non-medical exemptions. To ensure that vaccination policy improves immunization coverage and promotes public health, Washington should look to California’s experimentation with immunization policy. It is critically important to continue to enhance education and awareness of the threat of falling below herd immunity.

Increased monitoring of the exemption process, including medical waivers, is needed to maintain adequate coverage and protect individual and community health.

Additional resources:

- Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunization

- Parental refusal of pertussis vaccination is associated with an increased risk of pertussis infection in children

- Vaccine Refusal, Mandatory Immunization, and the Risks of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

- Health consequences of religious and philosophical exemptions from immunization laws: individual and societal risk of measles

Photo by Oksana Kuzmina/Shutterstock

Related Projects

-

September 15, 2016

|Has Evidence

| -

Mental and Behavioral HealthCalifornia Diversion: Mental Health, Racial Equity, and Criminal Court

September 1, 2021

|Has Evidence

| -

Community Justice and Public SafetyAre Cities and Counties Ready to Use Racial Equity Tools to Influence Policy?

December 15, 2018

|