Turning research into action: Promoting your work in a policy environment

|

“Evidence still matters. Regardless of where you are, who controls the statehouse, or who controls the administration. There’s still a tremendous hunger for digestible research.” – Kristen Gurdin, Assistant General Counsel, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Imagine the following scenario: Your research has just uncovered new insights on the population health impacts of a national safety net program. If the program was tweaked, thousands of people would see marked health improvements. Because of your expertise, legislators start asking you to assist in drafting amended legislation, and advocates seek your help in crafting talking points for their meetings with policymakers.

You see yourself as a source of objective, nonpartisan information (and not as an advocate), but still you hesitate. You know that your grant funding cannot be used for lobbying; how can you share your findings without stepping over that line?

A few months ago, some of our researchers participated in a training designed to help answer that very question. Here’s what we learned…

What exactly is lobbying (and how do I avoid it)?

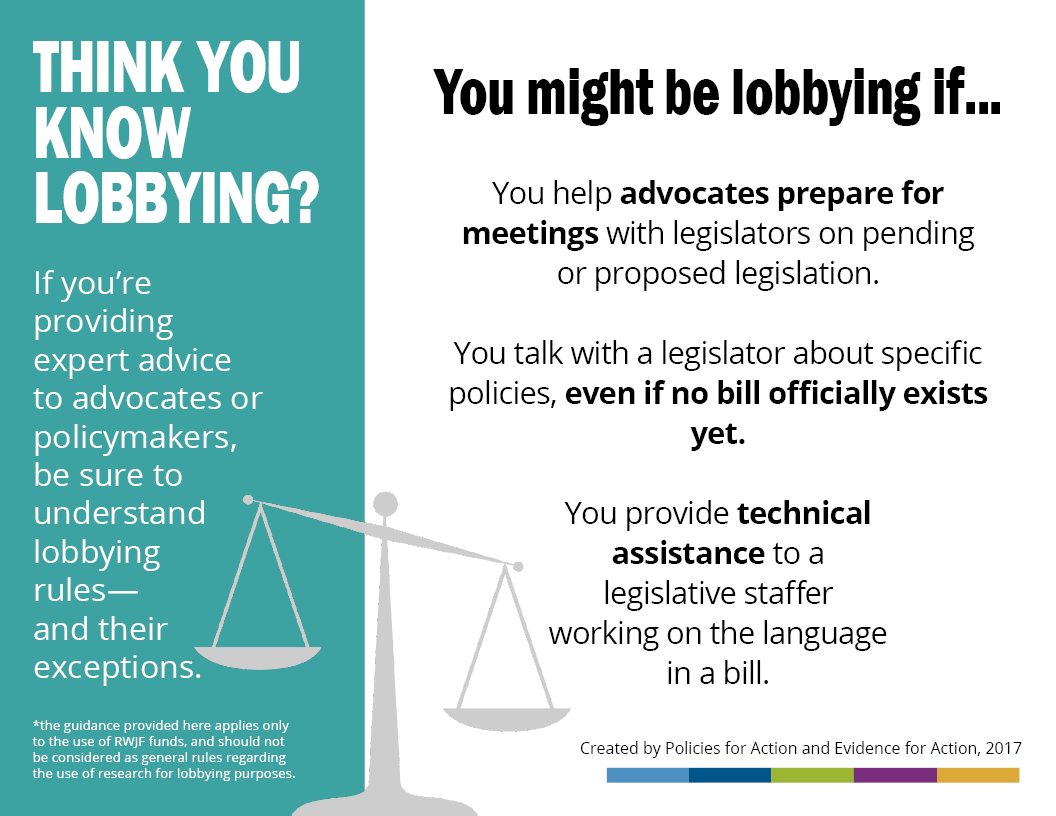

By law, private foundations like the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) are prohibited from lobbying or financially supporting any lobbying efforts of its staff, grantees, or other partners. Direct lobbying is defined as any activity that includes all four of the following elements:

- Direct communication

- With a legislator or staffer, or other government official involved in the formulation of legislation

- Refers to specific legislation (pending or proposed)

- Reflects a view (even a technical one)

For example, it is direct lobbying if you:

- Email a copy of your research paper along with a note to a legislator offering your opinion on a specific piece of pending legislation.

- But you CAN email a copy of your published, peer-reviewed study to a staffer interested in gaining background knowledge in your field of expertise.

- Initiate a meeting with a legislative aide while on RWJF funding time to discuss amendments to a specific piece of proposed legislation.

- But you CAN publish an op-ed explaining your research and its implications for a specific bill.

- You CAN also express views on administrative actions, like regulations and executive orders, in direct communications with policymakers

Non-partisan study, research, and analysis

As researchers working on high-profile policy issues, we must be thoughtful about the collateral we create to explicate, summarize, and promote our research. A communication product and the time dedicated to its preparation is NOT lobbying if it:

- Contains full, fair and objective discussion of the relevant facts sufficient to permit the audience to form an independent opinion

- Is broadly distributed

- Does not include a direct call to action (e.g., tell the audience to contact their representatives, or provide contact information or a means to communicate with their representative, such as a draft email, postcard or link to a petition)

- Has a clear, non-lobbying educational purpose at the time it is created

If materials are crafted to meet these standards at the time of release, they can be used in the future by multiple groups to inform emerging policy discussions.

Maximize your impact

To reiterate, researchers can—and should—have an active hand in promoting the findings of their research to inform the public and evidence-based policies. Here are three ways to maximize the policy impact of your research.

Leverage written invitations

Legislators routinely ask researchers to testify on a particular issue, or assist them in drafting specific legislation. Normally, these activities would be off limits. However, if you are asked to provide such input and you can secure a written invitation on behalf of the governmental committee, subcommittee or body prior to any involvement, you can engage in these activities without lobbying. To satisfy this exception, you must meet some clear requirements, so seek legal counsel or check out the recommended resources at the end of this post before using this exception.

Pursue unrestricted funding

If you anticipate large policy implications from your work, seek out unrestricted funding from other sources. Those unrestricted funds can be used for traditional lobbying, for requests from advocacy organizations, and more. Before doing this, understand your own organization’s lobbying limits and rules. (Note, there are also state and federal registration requirements for some types of lobbying activity and state institutions may, as a matter of state law, have certain lobbying restrictions.)

Get creative – ahead of time

As we have written before, policymakers, their staff, and other key influencers are hungry for information they can digest easily. In addition to publishing your papers, consider creating one-pagers, FAQ or talking point documents, model legislation or policy variations, infographics, op-eds, etc. These materials should be objective and balanced, serve a clear non-lobbying educational purpose and be broadly distributed to the general public as well as policymakers who both agree and disagree with the points of view expressed, and should not include a call to action. By creating these supplemental materials in advance, they can be safely used by policymakers and advocates in the future to inform policy.

Seeing it in action

As an example, let’s take P4A grantee Professor James Heckman and colleagues’ recent release of a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, “The Lifecycle Benefits of an Influential Early Childhood Program.”

In that working paper, the research team demonstrated that high-quality, birth-to-five childcare programs had the potential to deliver a 13.7% per child, per year, return on investment through better outcomes in health, education, and employment.

Knowing policymakers and other key stakeholders and influencers would not have time to read a 72-page academic article, the Heckman team created a portfolio of supplemental materials to promote the groundbreaking study. They assembled a stylized one-pager with striking visuals and key takeaways, an FAQ document to respond to common methodological questions, and downloadable social media graphics and sample posts. Additionally, the team organized briefings for media and advocates to explain their key findings.

Not surprisingly, the release garnered significant media attention, and continues to see traction nearly six months on. Most importantly, stakeholders and policymakers who wish to use this evidence to promote policies around early learning have everything they need to do so. These materials are available and accessible to everyone, including policymakers.

Why this all matters

RWJF invests in health and health equity research because it recognizes the need for a strong evidence base for the policies and programs needed to build a Culture of Health. As the research grows, and game-changing solutions emerge, it’s our responsibility to get that information into the right hands. Although policymakers aren’t the only ones able to act on the evidence, they are uniquely positioned to influence population health and health equity.

Ultimately, just as our research is objective and non-partisan, our approach to communication and dissemination must be equally balanced. We encourage our researchers to be cognizant of these principles as well as the legal restrictions so that their work stands up to scrutiny from fellow researchers, funders, advocates, and policymakers themselves.

Q&A

To close, here are a few common questions researchers often bring up when discussing these issues:

Q. Can I testify as a private citizen about an issue?

A. Yes. However, you may not use RWJF resources to fund your time preparing for that testimony or for creating the materials you wish to share.

Q. I want to promote my work through my organization’s email newsletter, but I know that legislators and staffers receive these communications. Is that a problem?

A. No. If a policymaker or their staff has affirmatively signed up for your listserv, and you are not targeting them specifically, it is not considered lobbying.

Q. Lobbying is defined as concerning “specific” legislation, but can I weigh in on a type of law that is commonly used to achieve a certain goal?

A. It depends. If you were to talk broadly about the use of a tax as a behavior inducement (e.g., increasing a cigarette tax to reduce smoking), that is not a problem. However, if you were to reference California’s recent cigarette tax hike as a model that North Carolina should adopt, it could be considered specific legislation. Discussing multiple legislative and regulatory approaches, without indicating preference for any particular strategy, is one way to address this.

Q. What resources are available to help me and my colleagues better understand these rules?

- Learnfoundationlaw.org is a free training resource that provides a one-hour interactive training on the lobbying restrictions that apply to private foundations and their funds.

- Influencing Public Policy in the Digital Age: The Law of Online Lobbying and Election-Related Activities, Alliance for Justice, 2011, www.Afj.org/digitalage

- Being a Player, Alliance for Justice, 2011, www.tinyurl.com/AFJplayer

NOTE: the guidance provided here applies specifically to the use of RWJF funds, and should not be considered as general rules regarding the use of research for advocacy/lobbying purposes.

Photo by Nicole S. Glass/Shutterstock

Related Projects

-

September 15, 2016

|Has Evidence

| -

December 1, 2020

|Has Evidence

| -

September 15, 2016

|Has Evidence

|